12-tips for designing better survey questions

The techniques I use to help ecomm brands, agencies, and Fortune 500s design survey questions.

“It would be a great error to assume that the only worry of the surveyor is the fear of being ‘unneutral’ in wording questions. Of even greater importance is the danger of being unintelligible.”

George Gallup

The Pulse of Democracy (1940)

The Tips

Make “omit needless words” your mantra

A list should be easy to scan, regardless of length

Ask about the home, not the head

You’re not irrelevant. Keep your opening remarks brief

When you should use social proof to get honest responses

Don’t ask “What would you pay?”—ask, “What did you buy?”

Write response options that sell

Aim for “question-response option” fit

Aim for “product-verb” fit in your customer satisfaction questions

Give people the chance to say “I don’t remember “I don’t know” and “not yet.”

Cut “metadiscourse” from your surveys

Every survey question should have a question

Never ask respondents to perform more than one task

Who’s guide is for?

Have you ever:

➡️ Needed quant data to support a marketing decision but struggled to find reliable and affordable solutions?

➡️ Relied on desktop research for insights, only to force-fit your findings to your narrative?

➡️ Used a social listening tool but found it to be underwhelming and overpriced?

➡️ Hired survey vendors only to get dull questions that lack the creative insight you needed?

This guide is for anyone who knows surveys are useful but cringes at survey jargon such as:

•“We value your feedback.”

•“Stay on the line to answer a few questions at the end of the call.”

•“How likely or unlikely are you to recommend our service to a friend?”

You’re here because you’re a marketer, researcher, founder, brand strategist, or ad exec who’s tired of mediocre survey outcomes.

So what’s the big idea?

Survey questions should be easy.

Easy questions allow people to simply share what they know, while hard questions force people to speculate.

When you prioritize ease, you’ll ask better questions.

That might sound obvious.

But searching “good survey questions” usually returns tips focused on accuracy, rather than ease.

This guide is designed to help you design questions that are clear and intuitive, without sacrificing on accuracy.

Every tip in this guide is informed by two disciplines:

#1: Thoughtful design 📱🖱️

Responding to a survey question should feel as intuitive as a thumb-scroll.

Excessive lists, lengthy response options, and poorly labeled scales make surveys clunky, and should be cut or shortened.

#2: Good writing ✏️ 🗒️

A survey question should follow the rule: “Omit needless words.”

A question like “Which of these factors influence your decision-making process when purchasing furniture items for your home?” might sound professional.

But it can be replaced with, “When you buy furniture, which factors do you consider?”

The benefits you’ll reap from a well-designed survey

✅ More valuable insights: Design survey questions that are insightful, even before the results come in.

✅ Compelling messaging: Craft survey questions that double as compelling headlines or benefit claims—just drop the question mark.

✅ Speed & savings: Design and deploy surveys quickly, slashing the usual fees and pass-through costs.

✅ Engaging presentations: Transform presentations that feature survey data into captivating TED Talks.

✅ Higher completion rates: Craft surveys so engaging, participants complete them willingly—no incentives needed.

✅ Sharper decision-making: Reliable shopper insights mean better strategies, more conversions, and increased business.

👇

#1

Make “omit needless words” your mantra

I’m not a grammar purist.

But I’d burn “Omit needless words” onto your laptop because few other settings invite as much jargon as the workplace.

For example, “What was your primary reason for purchasing today?” might look good on a slide, but it can be shortened to “Why’d you buy?”

Omitting needless words is a great way to increase your completion rate. If given the choice between deciphering a confusing question or leaving the survey, most people will leave.

❌

Mount Sinai, 2023.

This survey appeared as I was booking a doctor appointment.

The question can be shortened to, “Would you be willing to answer a few questions to help us improve our site?”

#2

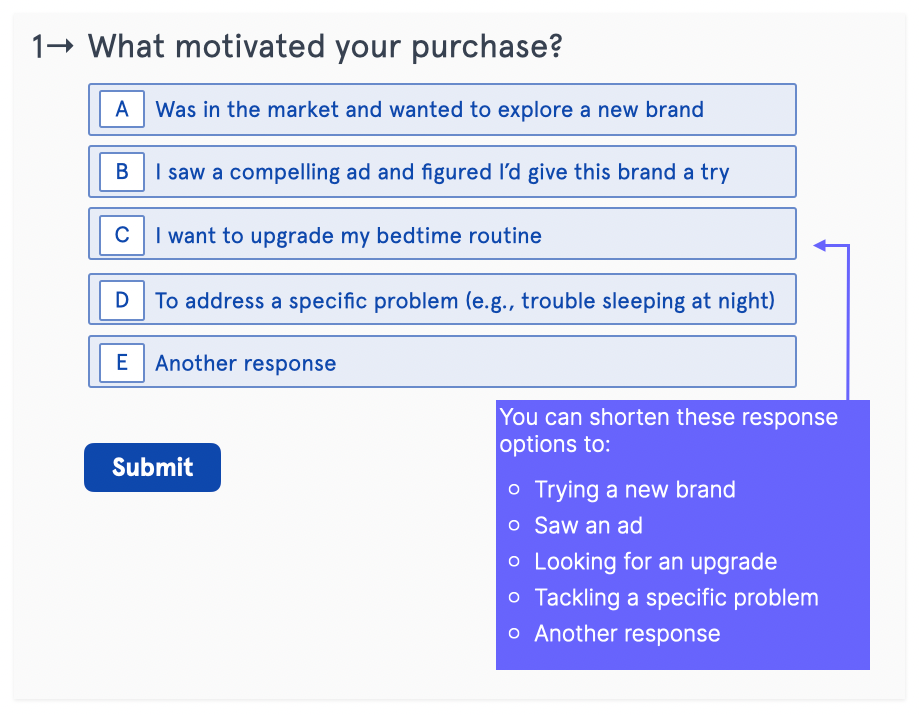

A list of response options should be easy to scan, regardless of length

People should find a response the moment they finish reading the question. If they have to search, they’ll leave or pick at random.

Long response options always have concise alternatives. “I saw a compelling ad and figured I’d give this brand a try” can be, “Saw an ad.”

A few other notes on response option lists:

👉 For familiar items (e.g., streaming platforms like Netflix or countries like the USA), sort the list alphabetically to help respondents quickly locate their options.

👉 For lists with unknown items where there is a definitive answer (e.g., "I'm here because I clicked on an ad"), place the most common responses at the top.

👉 For lists that include unknown items and solicit opinions (e.g., “Who dictates what’s culturally relevant?”), keep the list as concise as possible.

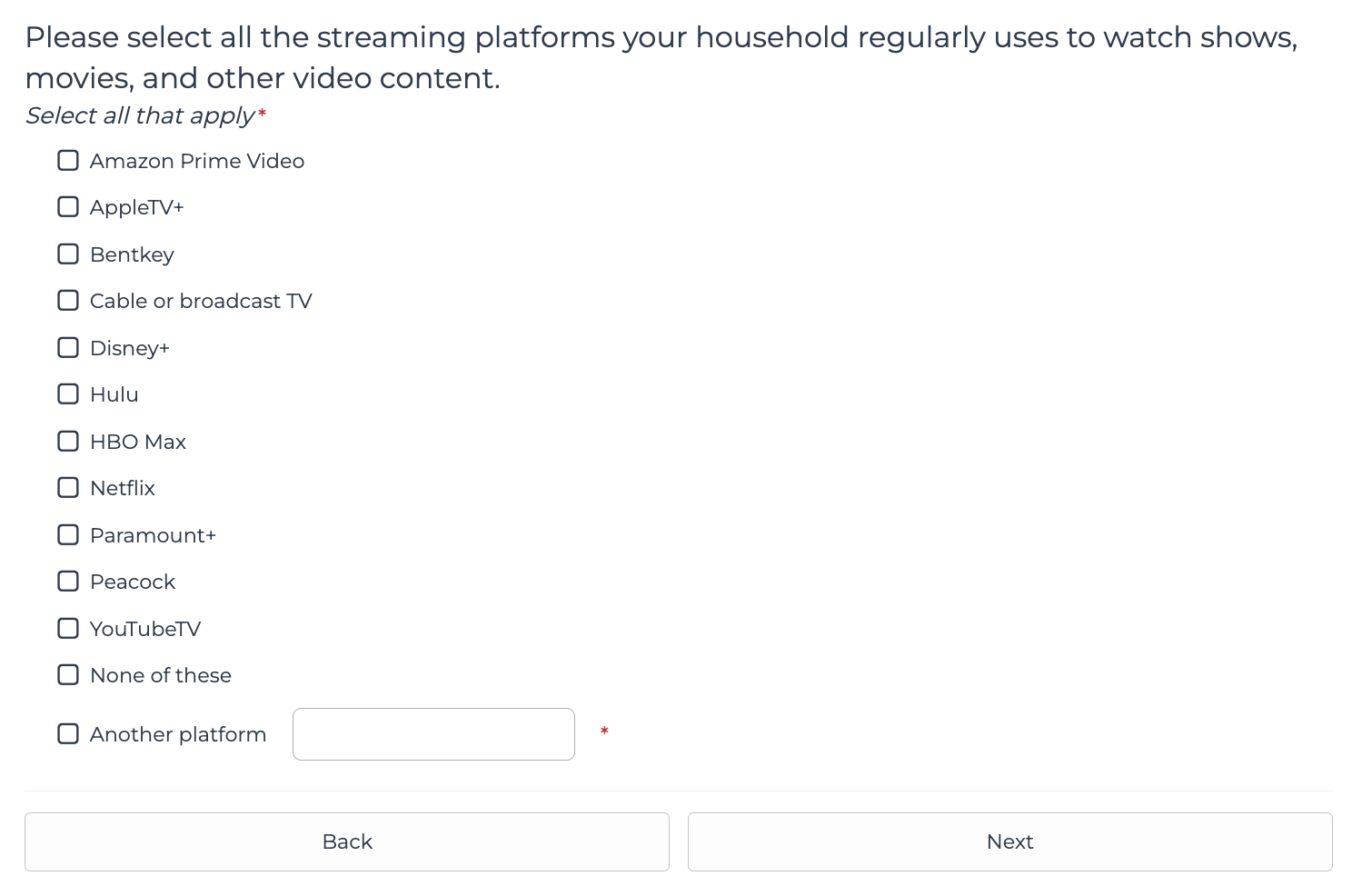

❌

New York Times, 2023.

This is a good example of a response option list that’s too long. I doubt anyone would read every option.

Each option is centered-justified, which makes scanning hard.

✅

Streaming Platform Research

This is from a survey I conducted for a streaming platform brand.

It’s a long list but easy to scan.

For familiar items like streaming platforms, I usually sort the list alphabetically.

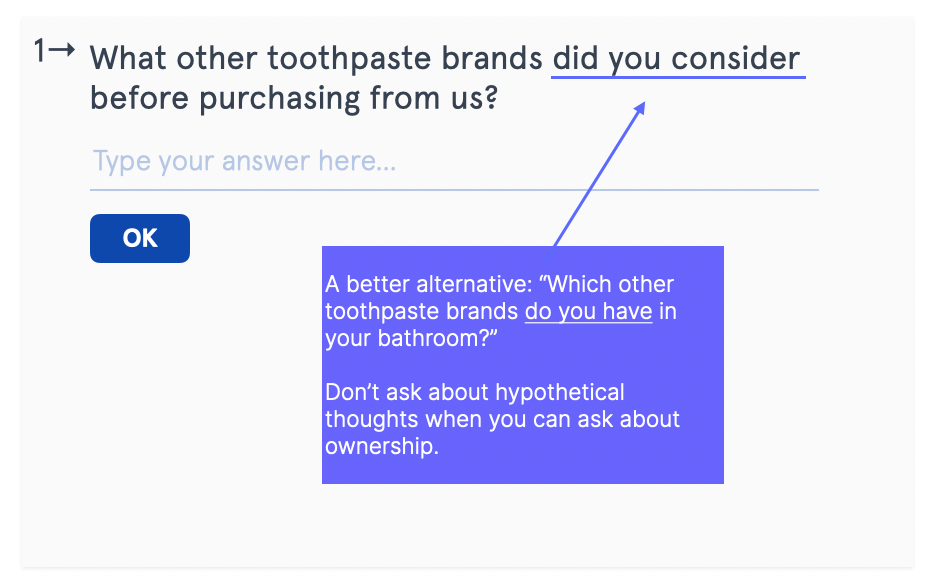

#3

Ask about the home, not the head

Why would you ask a shopper what they considered buying when you can ask them what they already own?

Since not everyone “considers” other brands before a purchase — and those who do usually struggle to remember what they considered — the question "What brands did you consider…. ?" is both presumptive and hard.

Focus on what people actually use, own, and do.

✅

Squarespace, 2023.

The first question, "Are you leaving for another site builder?" addressed my actions, which made it easy to answer (since I was just canceling an old subscription I no longer used.)

The second question, "How likely are you to recommend Squarespace…?" addressed my opinion, which was harder to articulate.

#4

You’re not relevant.

Keep your opening remarks brief

I was waiting to take off from Sarajevo to Warsaw when the pilot began a lengthy announcement in broken English about “busy airspace over Hungary.” I sat there wondering, "How long will the delay be?"

That moment always reminds me of a common survey faux pas: long-winded introductions.

Often well-intentioned, they just make people impatient.

👉 Keep your introductions brief.

👉 Mentioning the survey’s length is good practice, but not essential (see Bellroy example below).

👉 Be transparent. Does your survey involve multiple-choice questions? A writing task? People are more receptive and patient when they know what to expect.

✅

Bellroy, 2022

I've always liked this solicitation from Bellroy, an Australia apparel brand.

The question mark leading to the call-to-action is clever.

I also noticed how that they called it a "subscriber quiz" instead of a "survey.”

❌

Wells Fargo, 2019

A survey solicitation I received from Wells Fargo.

The button I needed to click was beneath the fold, under legal text about the chance to win $1,000. I assume the bad placement significantly decreased click-through-rates.

#5

When you should use social proof to get honest responses

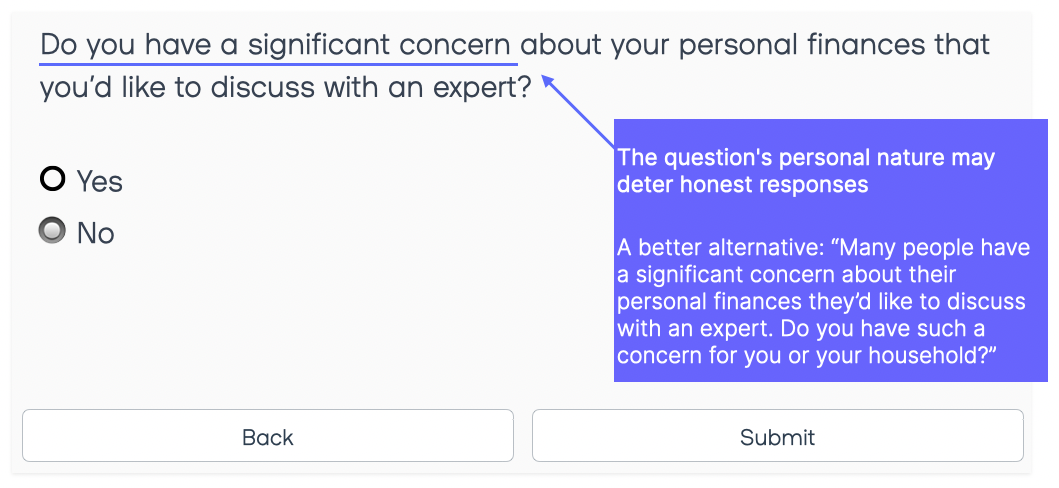

Sometimes, intentionally biasing people is good survey design.

For instance, in a test survey for a fintech brand, not one of the 15 respondents acknowledged having a “significant financial concern,” despite earlier research showing that most of us do.

In a revised version, we replaced “Do you have a significant concern…. ” with “Many people have a significant concern….” We also removed the line “... that you want to ask an expert because you can not find one,” which may have deterred respondents.

These changes led nearly half of the respondents to answer "Yes," which helped the client understand where their customer needed help.

#6

Don’t ask “What would you pay?”

— ask “What did you buy?”

When it comes to money, avoid speculative questions such as “What’s the maximum amount you would be willing to spend on a winter coat?”

It’s hard for people to predict what they’ll spend, both in a survey and while shopping.

Focus on actual purchases. People probably won’t remember exact amounts, but they can share a reasonably accurate estimate.

(Remember to include an “I’m not sure” option to accommodate people who don’t remember or received the item as a gift. See tip #10.)

#7

Write response options that sell

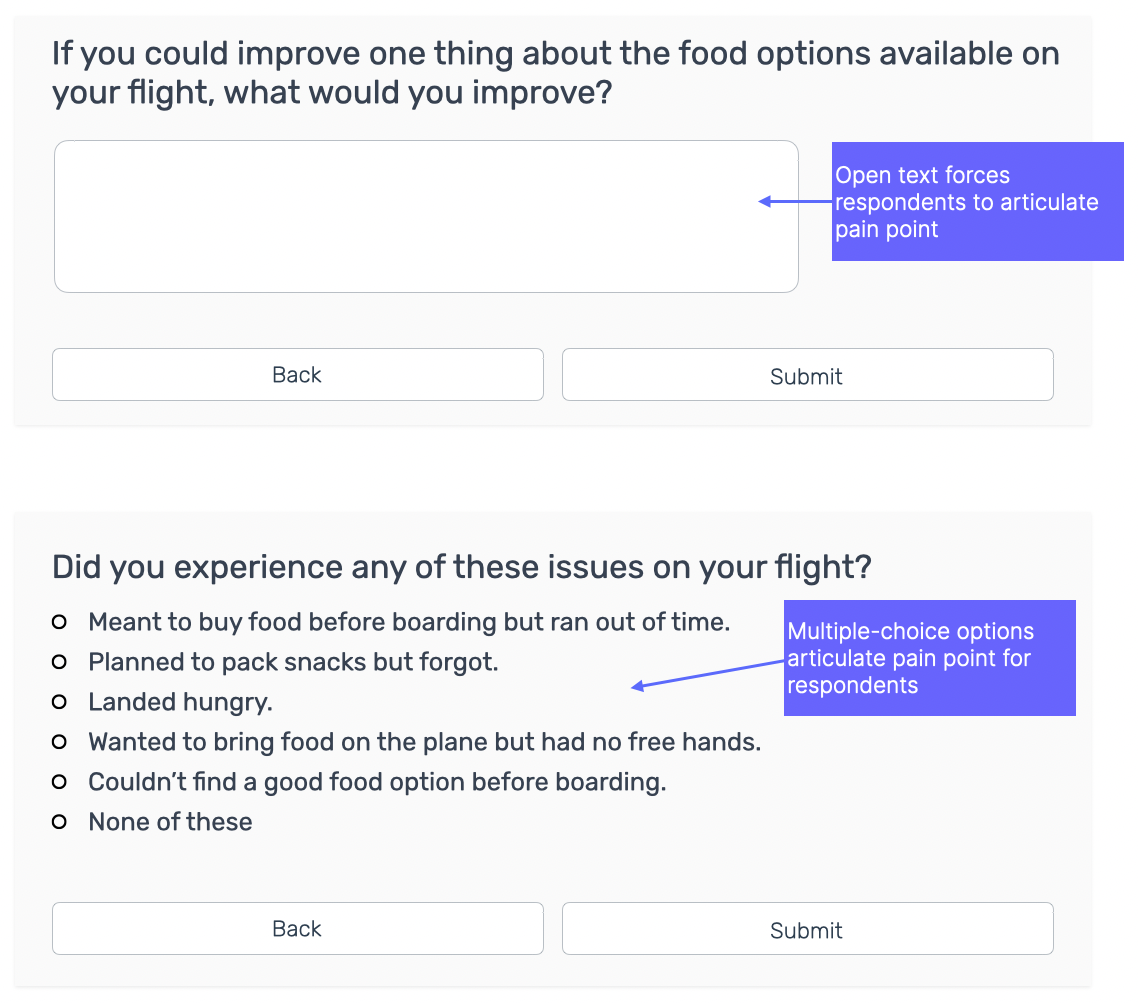

Researchers try to understand rather than sell.

But if you’re asking about a topic people rarely think about—and may have little to say—pretend you’re writing a sales letter.

The goal isn’t to persuade. It’s to articulate the half-formed thoughts and opinions that people won’t take time to express for themselves. Avoid open textboxes and use multiple-choice instead. Try to give people an option that makes them think, “Yes, that’s exactly how I feel.”

#8

Aim for question-response option fit

I once read that good writers have an “elusive ear” that they use to spot jargon and confusing sentences, but you don’t need extensive writing practice to see when a response option does not “agree” with its question.

I was once asked by a survey platform how “likely” I was to recommend the platform to a friend or colleague. The options ranged from 0, labelled “Not a chance,” to 10, “In a heartbeat.”

While selecting “10” clearly indicated an endorsement, there was a mismatch between “likelihood to recommend,” which measured probability, and the label “In a heartbeat,” which measured enthusiasm and immediacy.

✅

Viagogo, 2023

Notice the same verb in both the question ”Is this your first time seeing Hans Zimmer?” and the response option, “No, I’ve seen Hans Zimmer before.”

❌

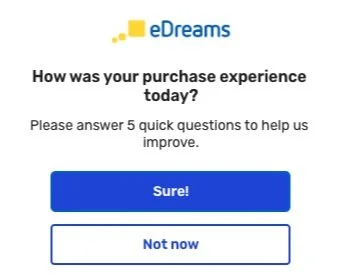

eDreams, 2023

This popup features both a question (“How was your purchase experience today?”) and a request (“Please answer 5 quick questions to help us improve”).

“Sure!” might work for the request, it doesn’t fit the question.

#9

Aim for product-verb fit in

your customer satisfaction questions

The reason some surveys provide valuable feedback while others spew out worthless garbage sometimes lies in just a few words.

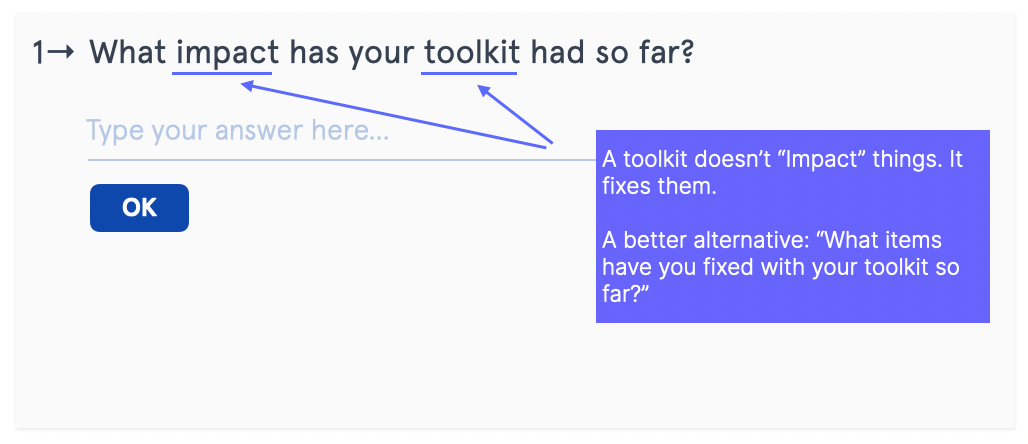

Look at the question in the image: “What impact has your toolkit had so far?”

The world “impact” is associated with collisions and measurable outcomes, not what toolkits do, which is fix things.

The question should be, “What items have you fixed with your toolkit so far?”

#10

Give people the chance to say “I don’t remember” “I don’t know” and “Not yet.”

This is especially true if you’re asking about the distant past, or anything people could forget, such as where they discovered a brand.

Without “I don’t remember” as an option, respondents who don’t remember may either respond by randomly selecting or choosing not to answer at all.

Marketing 101: when people don’t see an option that fits, they leave.

✅

Ticketmaster, 2023

Despite my disdain for Ticketmaster and their hefty “service fees,” I appreciate them including “not yet” in this onsite popup survey.

It was my response to their question “Were you able to accomplish your primary goal on this visit?”

❌

Bose, 2022

Bose stands in contrast to Ticketmaster.

They both asked the same question. But Bose did not include “Not yet”—a choice that would have been my answer.

#11

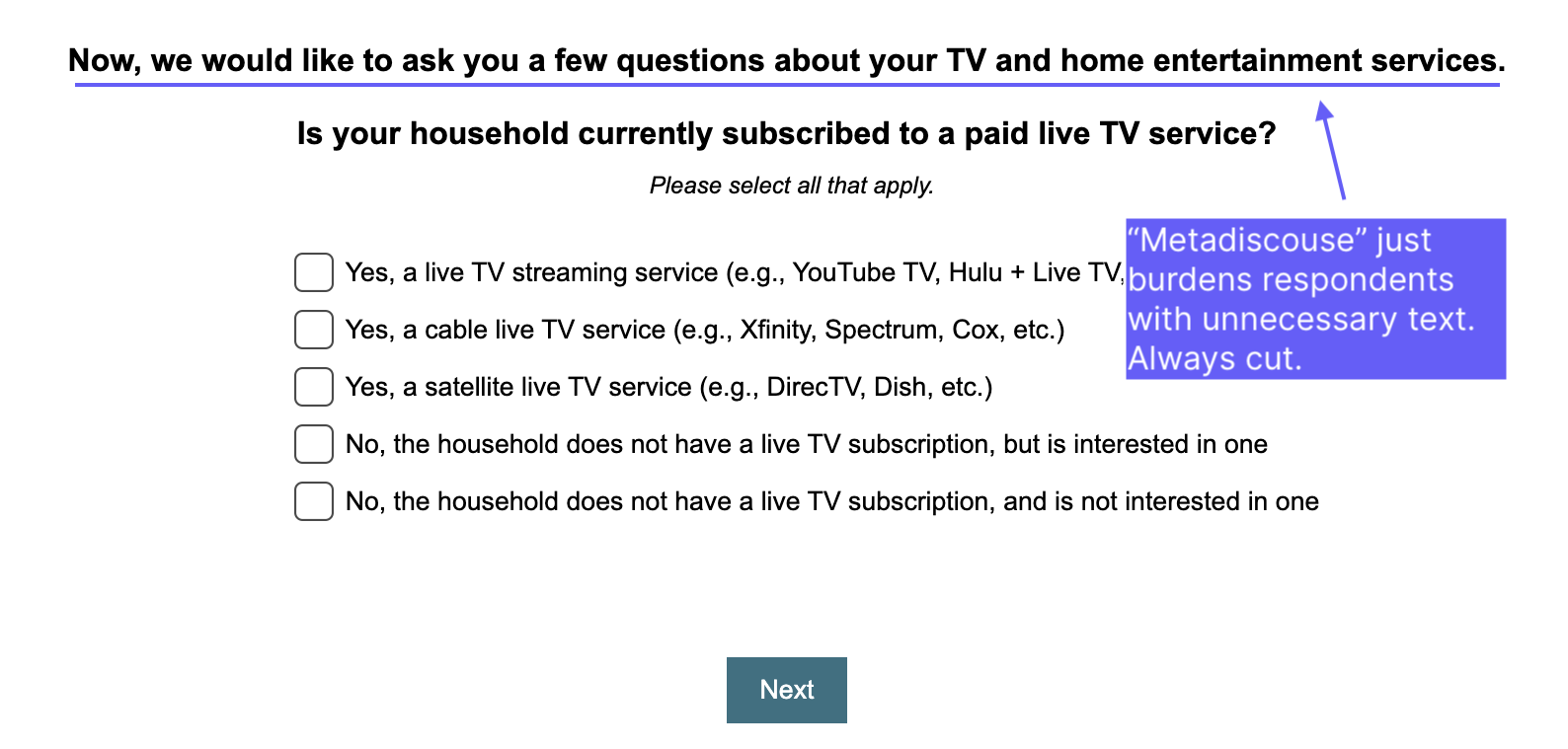

Cut “metadiscourse” from your surveys

In The Sense of Style Steven Pinker talks about “metadiscourse.”

It’s when writers talk about the act of writing itself, using phrases like “First I will discuss X, then I will move on to Y.”

Metadiscourse is unnecessary guidance. It burdens readers, and it should never appear in your surveys.

In the image above, the sentence “Now, we would like to ask you a few questions about your TV and home entertainment services” is a good example of metadiscourse.

Since respondents already expect to answer questions about these topics, YouTubeTV doesn’t need to state what it “would like to ask.”

Instead, they should follow a rule of thumb I’ve stapled to my desk:

Always focus on the topic, never on the act of asking about it.

#12

Every survey question should have a question

Writing a survey question without asking a question may seem impossible, but it happens more often than you think.

Check out the prompt in the image above: "Passing on UserInput? We'd love to know how we can improve."

While it's clear they are seeking feedback, there’s no question being asked. “Passing on UserInput?” is rhetorical and “We’d love to know how we can improve” is a statement.

Adding to the confusion, the response options don't fit. The option, "It's too expensive for me" doesn’t make sense as a response to either “Passing on UserInput?” or "We'd love to know how we can improve."

The question should be, "Why are you passing on UserInput?"

As in: “Why are you passing on UserInput?” → “Because it’s too expensive for me.”

#13

Never ask respondents to perform more than one task

The problem with "two-part" questions isn't that people are forgetful; it’s the strain of holding one question in mind while answering another.

A similar tension is felt in survey questions with more than one task.

Take, for instance, a LinkedIn survey (shown above) where I was asked "If you could improve one thing about a LinkedIn tool or products, what change would you make?”

The broad question was daunting. So was the large empty text box.

I didn’t know what a “LinkedIn tool” referred to, and the shifting phrasing within the question — from “if you could improve one thing…” to “what change would you make”— added to the confusion.

However, the worst part was that I was expected to list the product, be as specific as possible, and avoid sharing personal information.

It was one of the most difficult survey questions I've seen. I selected the somewhat hidden "prefer not to answer" option.

Thanks for reading!

Sam McNerney

Founder, McNerney Insights & Marketing